Eight World-Class B-boys and B-girls Speak Their Minds

By Rick Tjia

We live in a turbulent world.

We live in a new era wrought by war, dissent, separation, and pandemic. But war is not new. Dissent and separation, even pandemic, has happened before.

And yet we live in an era we call new. In as much as we live dissent and separation, we also live in a world of connectivity and technology, factors that feed both. It has often been art that allows humanity to brave the storm, art of all kinds. In fact, if you were to look around you, nearly everything you see— performances, paintings, photographs, buildings, cars, the color of your walls, even the chairs you sit on— have had an artist’s hand in it in some way or another.

So the newness of the era comes, perhaps, from a difference in style. A difference in connectivity, a difference in culture, and a difference in accessibility to that culture. Technology has made it so that access to information and culture today decidedly takes much less time and effort than it did 30 years ago.

Less, but not zero. Without a minimum of time and effort put into finding both, nothing will have really changed.

So we dig. One thing that has not changed is the idea of “to each his art.” For many of us, that art is dance. There are paintings that record evidence of dance as early as 10,000 years ago in India. Since then, there have been many forms of dance that have come into being, forms of dance that have been around for a very long time.

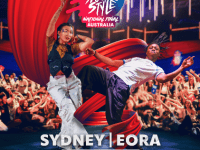

Compared to other dance forms, though, breaking is a very young discipline. It materialized through hip-hop culture, a culture emerging from a mix of styles and whose modern form was born at a famous party event at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx on August 11, 1973. At the time of this writing, that’s almost exactly 50 years.

And in the 50 years following this Bronx party that started it all, the “game” we call breaking— as it has been called by Jack Rabanal, aka B-boy Hijck— has been adopted by many countries and many cultures. And, as all cultures inevitably do, it has evolved in various ways. Not everyone approaches it the same way, and not everyone plays the “game,” or even looks at it, with the same mindset. In fact, though the origins of breaking are undeniable and remain uncontested around the world, the answer to the question of who is at the forefront of its evolution today sparks some very, very different opinions.

Asia One, who is an American and an OG in the breaking world, feels that dancers’ origins play a role in how one sees the discipline. “I think we as Americans have the benefit that hip-hop actually started out here. Whether we’re attached to that or not, it’s just a fact and that people closer to that root like in New York are going to express this dance in a way that a lot of people won’t be able to.”

B-boy Kareem steps this up a notch. “To be as frank as possible, most people are trying to either beat USA or be USA,” asserts Kareem. “It’s rare that you see a dancer from let’s say Europe or Asia that influences breaking so much that the USA breakers want to be like them… I can name some crews for sure, but throughout it all you can’t get any better than when it’s homegrown, you know what I mean?”

The sentiment is understandable, but it is a sentiment that is not necessarily shared equally by everyone across the globe.

“America created a lot of things,” says Ukraine’s Katya Pavlenko, aka B-girl Kate. “They created hip hop, they created house music, they created a lot of things. Then Europe just takes it and puts it up to the next level. And that’s what I think happened with breaking too. It was super dope, super cool before, in America, when it all started. And I think like in the 2000s—like 2010 and after that, Europe started just improving whatever they created.

“They’re a little bit relaxed In USA,” she continues, “a little bit chill. They think they’re already cool just because they’re from the USA. Not all of them think like this, but just overall I feel a little bit like this.”

Canada’s Luca ‘Lazylegz’ Patuelli adds, “I’d say Europe and Asia have a much more disciplined approach than North America. And I think North America now, because of the Olympics, they’re starting to change their approach to be a little bit more like Europe and Asia.”

Even Asia One admits that in the US there are some of what she calls “downsides.”

“We’re a little bit lazier than people in other countries, just naturally. I’ve noticed in my travels, people can be a little bit… like, you go to Asia and people are way more disciplined in places like Japan, Korea.”

“People here are more creative,” says Hijck about the United States. “This is the birthplace. The US is the birthplace of this dance. But it’s something about the outside international cats that just—it remains almost in a sense more true. You know, like there’s more essence to it. They’re more about like the footwork and the power and stuff, and really ‘creating their own,’ as Poe One would say, creating their own fingerprint within this dance.”

More creativity would tend to suggest more diversity and less homogeneity in the development of the stylistic, the artistic, outcome. But is this what we’ve been seeing coming from the USA over the years since breaking’s inception? Czech Republic B-boy Kristián Mensa, aka Mr. Kriss, adds a question mark to this.

“I spent a year in Colorado in the United States when I was a teenager,” Kristián explains. when I was 16. So I had an amazing opportunity to be part of the community. And I would say, of course it’s (US vs Europe) based on very similar pillars, or you know the ground is very similar. But some small details are different.

“In the United States, I kind of felt almost the same approach within most of the country.”

More homogenous, not less, which would seem to contradict Hijck’s interpretation. But it is interesting, such varied views on the same things: if different people from different cultures see different truths while observing the exact same thing, the next question that comes to mind is: Why would this be?

Any opinion can be considered “truth” with respect to the angle and context from which something is observed—because each observer observes within a context that is personal and built upon that individual’s unique background and experience. Opinions are built upon extrapolations and deductions based on multiple realities that may not even resemble each other.

So it may be a bit simplistic to chalk up a global explanation of a universal phenomenon through simple one-line explanations like “lazy,” “creative,” or “everybody wants to be like us.” I suspect, as with most things, that individual realities are quite a bit more complex than this.

“If I were to compare the Czech Republic with Colorado where I spent a year,” adds Mensa, “I would say the Colorado dance community is much more connected than the community in the Czech Republic. They have more open sessions, places where you can go to practice. Whereas here, at least in this country, it’s a little more dissolved into groups, and it’s a little bit hard to find a place that is open for everyone.”

There are also other differences in the culture of breaking in different countries that are more subtle and perhaps unnoticeable— unless you have either been immersed in the culture, or at the very least, have experienced it often.

“In Europe they usually, let’s say like in Marseille, they’ll have a bunch of families there,” says Kareem. “There’ll be majority families there, watching the competition. In North America, It’ll be a bunch of our peers watching the competition. So, as a culture, yeah, it’s totally different.”

“I think in Europe what I’ve experienced too,” says Asia One, “is we in the US now, we’ve been somewhat sensitive to male and female in this, whereas in Europe I don’t sense that as much. It’s just the dance. So a woman is going to be sized up like a man, the same way that a man would be sized up.”

She explicates. “Over here (in the USA) people kind of label it more. I think men kind of still feel like, ‘Oh, that’s a woman. I’m not gonna exhibit the same aggression as I would to a man.’”

Yes, these observations are most certainly tied to cultural aspects. But there are other external forces that may account for some of the differences as well, differences that, while still cultural, transcend artistic ideology altogether. In particular, the elephant in the room: economics.

B-girl Isis is a breaker from Ecuador. “In my country,” she says, “we have support of the Federation—but just like saying, ‘Yeah, we support you.’ But there’s no spot for training… there is like nothing to really support us, you know.”

“When in South America you don’t have much opportunity to be traveling, competing internationally,” says Neguin. “It just, like, becomes a dream for those kids, like I was back in the days, you know?”

Some countries do support the art financially—which suggests that the international playing field may not necessarily be even.

“I think that you have that motivation that dancers in Europe can make a solid living just off competing and performing, compared to North America,” says Patuelli. “And I know In Asia, at least in Korea, that if you become a dancer at a certain level, the government supports you.”

“The daily living worries are less for dancers in Europe and in Asia compared to in North America,” he continues, “where many of these dancers most likely have full-time jobs or part-time jobs, or are students. And then they’re dancing on the side.”

What comes to mind from hearing these varying viewpoints is the old saying, “Don’t judge a book by its cover”— except with a component that is much deeper than that, because when you talk about culture you talk about two specific identities: the identity of a people, and that of the individuals within it. The two identities are linked, but they are not the same thing. An individual is influenced by his or her culture, but is not necessarily defined by it.

This is an important distinction to make, because when you dig into one, you can begin to understand a general mindset and approach to breaking that could explain a lot of things that hitherto did not seem to make sense. But when you dig into the other, you may begin to understand what makes an individual unique.

Differences stimulate debate. And though in recent years we have seen an unfortunate trend of debates tearing people apart, it is also, ironically, debate that brings communities together.

So why would you enter the world of someone who is completely different from you? To argue your point. And it is only by arguing points that minds can be changed.

Or that understanding can be reached.

Rick Tjia

Many thanks to the b-boys and b-girls who agreed to be interviewed for this article (in alphabetical order):

- Asia One, USA

- Hijck, USA

- Isis, Ecuador

- Kareem, USA

- Kate, Ukraine

- Lazylegz, Canada

- Kriss, Czech Republic

- Neguin, Brazil