The Original Tap Dog Still Inspired to Teach Future Tap Pups

Interview with Dein Perry

A conversation with Chris Duncan

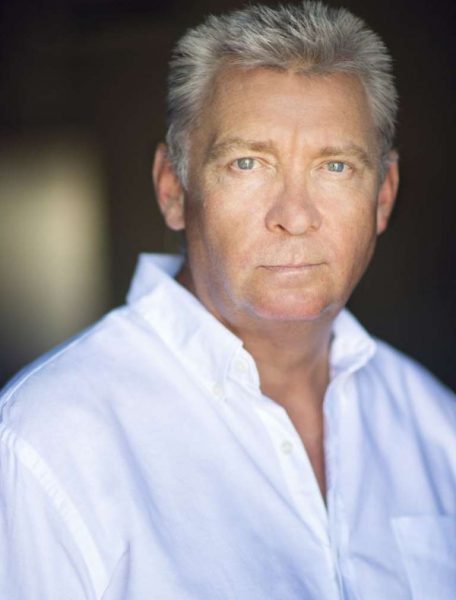

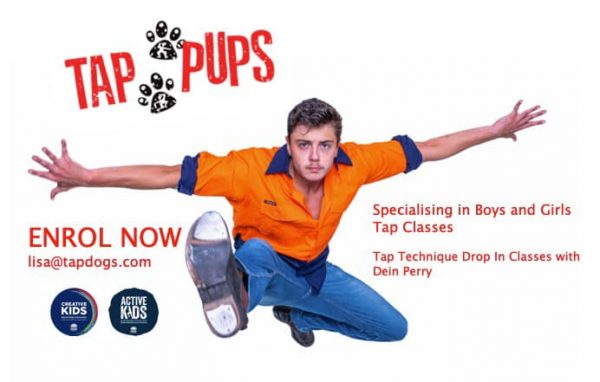

Today’s dancers may have heard of the Tap Dogs but they are probably unaware of just how much of a dance phenomenon the six blokes in tap boots were around the world in their heyday of the 1990s. Acknowledged for revolutionising the genre of tap for a new audience, the founder of Tap Dogs, Dein Perry, is still as passionate about the artform as ever and has had the pleasure of ushering in several new generations of male tap dancers, which has aptly been dubbed the ‘Tap Pups’.

Today’s dancers may have heard of the Tap Dogs but they are probably unaware of just how much of a dance phenomenon the six blokes in tap boots were around the world in their heyday of the 1990s. Acknowledged for revolutionising the genre of tap for a new audience, the founder of Tap Dogs, Dein Perry, is still as passionate about the artform as ever and has had the pleasure of ushering in several new generations of male tap dancers, which has aptly been dubbed the ‘Tap Pups’.

From his legendary rise to international fame from being a fitter-and-turner from Newcastle, many do not know of how Dein navigated his path to success from such an unlikely background. In this conversation with DanceLife Editor-in-Chief, Dein shares his story of how he grew up competing in Eisteddfods before giving it all away – as most male dancers do – to work a regular job driving trucks before getting his first dance gig in Tasmania. Then, in Sydney he did everything from teaching tap to performing at shopping centres before getting his big break in the musical 42nd St. Soon after, his creative destiny seemed certified when he teamed up with another great Australian tapper, David Atkins, to tour Hot Shoe Shuffle in the UK. From this, the idea of Tap Dogs was born and Dein returned to his Newcastle mates to make this new tap show a reality.

Twenty-eight years later, Tap Dogs has cemented their place in history, spawned a Hollywood movie, is still performing shows around the world and has an alumni cast list that reads like the best-of-the-best male tappers in the world. Dein is proud of his part in re-invigorating the tap scene in Australia which has produced a current cohort of young tappers that are now carving their own niche in the performance world. Despite setbacks due to COVID he is keen to see the next generation of tappers continue his tradition of bringing power to boys who dance when touring can be started up again with the Tap Dogs companies. In the meantime, Dein is excited to personally teach young boys, and girls, and impart his passion of tap at his Tap Pups studio in Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

Please enjoy our conversation with Dein Perry.

***

CD: How have the last couple of years with COVID treated you?

DP: Well, probably the same as a lot of other people. I mean, the entertainment industry basically just came to a grinding halt and we’ve struggled really for the first time for a long time. It put our show on complete hold. Even now it’s too risky to look at touring. So, maybe taking a chance with little one-offs shows and there might be the way to go for the time being; but with shows of our calibre and size, it’s really hard to take a risk because they can close overnight and you are just at a loss.

So, we’ve been just kicking on and our studio keeps opening and closing. I do a lot of entertainment in the sports arena so that has kept me alive to be fair. But even that comes and goes…. You’ll be in the middle of a tournament and all of a sudden it could stop. Like, I was just doing the BBL cricket and we lost the last couple of matches because all the players had to move into a hub because of Covid. Same with the NRL last year, halfway through the season work stopped and the season before that we got cancelled.

I know a lot of people in our industry get a bit cranky about how sports seemed to get special exemptions over arts, but really I think that with the NRL especially, they really led the way back for events. And there are a lot of people in entertainment that work in sport as well. They sort of showed how it could be done during COVID for other events, and I think they did a pretty good job. They pushed really, really hard to get the games back.

But I suppose at my age it’s probably okay. We got a little bit of help from the government, so I pottered around the house doing things that I would never normally do.

CD: A little bit of a forced semi-retirement after your career?

DP: Well, you know, when you are sort of getting up there in age, this is quite nice. We all work hard all our lives … nothing comes easy. The success of Tap Dogs never came easy. It was a push and a struggle and I was probably 33 before it started to hit its straps. And then you work very, very hard to maintain it. So having that bit of time off over COVID was the first time I think in my life I think I’ve actually sat back and realised I’m not allowed to do anything for three months. It then of course it happened again and again, and there was nothing we could actually do!

CD: I understand your trepidation of getting back on the road with such a large production being risky.

DP: It seems to me the big shows … they’re obviously getting some government backing and they get sort of bailed out. I suppose that makes sense when they have to close overnight and they’ve got massive casts and crews. But for the smaller shows, like our show is 15 people on the road, you just can’t tour anyway. But I suppose people in our business, the entertainment industry, have always been flexible because we’ve always moved from job to job. I mean, that’s how you have to work. You have to have some sort of business brain of course to be able to keep yourself employed. And a lot of us are used to that, but it’s never been anything like this before with COVID.

CD: Many of our readers may not know about the history of Dein Perry and Tap Dogs, so can you take me back to where it all began for you?

DP: Growing up in Newcastle, I originally did an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner, and I drove trucks for a little while too. But I wasn’t employed as a dancer until I was 21 when I got a job in a show in Tasmania. They gave me a bit of a tap solo because they saw that I could tap really well but and I was pretty crap at all the other forms of dance. In those days there weren’t as many boys around, so I managed, and the jobs were more accessible I think for guys then, for sure.

Then I moved to Sydney and I had a five-year plan to get into a professional musical. So for five years exactly I did gigs at theatre restaurants, in Humphrey B Bear suits, Chatswood Chase shopping centre pantomimes at school holidays, and lots and lots of teaching at different various schools. Until I finally got into a musical as a swing in My Fair Lady, which was a Victorian State Opera production and my first big contract. I covered eight guys in that show as a swing. From there I got roles in The Man of La Mancha and 42nd St. That’s when I picked up a good agent good, because I got good reviews in 42nd St. And that was my big break I guess!

I applied for a grant from the Australia Council to develop tap dancing in a more contemporary way. My vision was basically from watching Gregory Hines and Stanley Clarke playing bass; and what he was doing with tap was like ‘wow!’ Tap doesn’t have to be this old style stuff. So I played around, put some videos together, asked some people to come in and create some routines with me. We put it on video, included a handwritten letter to the Australia Council and forgot all about it. About six months later I got awarded about $18,000, which was quite a bit of money back in 1988.

So that gave me an opportunity to hire a studio, six dancers, two musicians and a video company to film it at the end of a four week workshop of ideas of different contemporary tap. At the time I hired David Atkins’ studio for the filming, which was called Dynamite, and I was teaching there at the same time as well. He approached me about doing a musical with him that he was thinking about called Hot Shoe Shuffle. So the six guys I had in my grant video, which I called ‘Real Tap’, sort of transferred over into Hot Shoe Shuffle but then they were called The Tap Brothers. My brother and myself were obviously in that and we also did a few jobs as The Tap Brothers.

So then I had a massive decision to make, because my 42nd St stint was great for me, it had been a real big success for my career. It put me on another level. After 16 months in Sydney (that’s how big the show was!) they were going to tour Australia, which would have been another 12 months. So, I could do that or take a chance to try and choreograph something with David Atkins where I would be co-choreographer. I remember just losing sleep tossing and turning on the decision to make. In the end I decided to go with Hot Shoe Shuffle and ended up going all the way to the West End. We even won an Olivier Award for the choreography.

So if I hadn’t made that decision to take a chance and leave 42nd St, I don’t think there would have been any Hot Shoe Shuffle or Tap Dogs … definitely not!

When I was in London performing Hot Shoe Shuffle, the Sydney Theatre Company sent a director over to talk to me about developing Tap Dogs, and I got offered from the ABC to do a five-minute filler program called ‘Performance Space’. So we made a little film and it was called Tap Dogs, and after they saw that they asked me if I was interested in developing that into a show for the Sydney Festival, because STOMP were also coming out and they wanted us to be a double act.

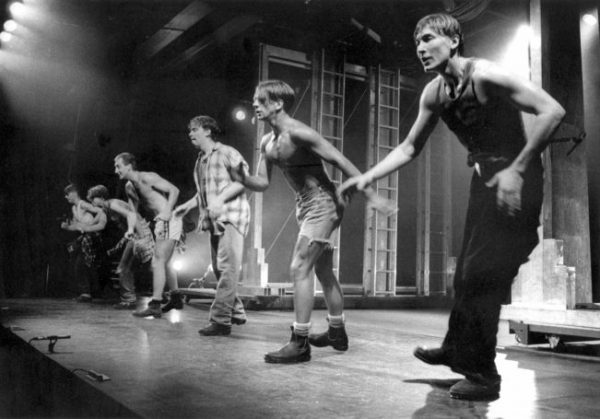

So I left Hot Shoe Shuffle, which was really hard to do too, because that had years of touring left in it, to try and start all over again. And a lot of the guys were happy to stay in the show too. That’s when I rang up Darren Disney who I’d known since I was six years old, because we were at the same dance studio and we competed against each other in Eisteddfods all our lives as kids. So I rang Darren and a few other guys in Newcastle that I knew could tap. That was probably the ‘raw edge’ of Tap Dogs as those guys weren’t in show biz guys, but they you know, they were different, they just looked like just normal fellas with dancing feet down below. And that’s how Tap Dogs started.

We opened at the Starfish Club. STOMP was on first and we came on second. And the moment we opened the phones for bookings, the phones at Sydney Theatre Company went into meltdown! This is a true story; they went into meltdown and completely clogged up. We sold out three weeks in about two or three days. We even beat STOMP in sales. And then that was it. We had producers coming in every night watching, trying to get the rights to the show. We went to Adelaide, the Edinburgh festival and found our international producers there. Then Tap Dogs just kept touring.

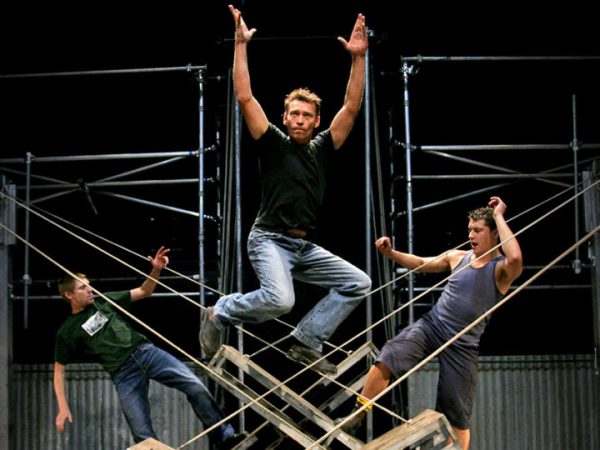

We had five companies at one stage. By the time we got to New York, we toured through America for six months just to get awareness and get onto all the big TV programs like the Jay Leno show and Ellen … just to get a name for ourselves before we opened up in New York. We played in New York for six months. While in New York, we cloned the companies and that’s when we put a company in London to tour the UK, two companies in the US, and one back in Australia. We never advertised it as, but it funnily enough it was dubbed as Tap Pups, because all the performers were younger guys in Australia. And then it just kept rolling along.

CD: Newcastle is considered a tap dance capital, but who influenced you in terms of your tap style and why do you love tap so much? What made Tap Dogs special?

DP: My mum loved tap and always wanted to tap but didn’t have the opportunity when she was growing up. She loved Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire and all of those old dance movies. So when I was four, she took me to tap class. I remember at the start of the year I would never like it because I wanted to be playing soccer or footy with the other guys. But then once I did Eisteddfods, I had all these friends that I’d only meet within those school holidays. They came from all different parts of Newcastle, and then people would come up from Lithgow and Sydney to compete in Newcastle Eisteddfods. And so there was this family that you have at the Eisteddfods in school holiday periods. So you’d have all these friendships from dancing and then you’d be really sad when the Eisteddfod finished and then you’d go back to school.

I trained until I was 16. And then I gave it away completely and went and did my apprenticeship and worked. But I think when I was doing 42nd St and seeing Gregory Hines in White Nights, I started dancing again and manipulated the style that I’d learned. I remember getting videos and slowing his feet down, trying to work out how they were getting around these incredible rhythms and different technique that I wasn’t taught. And he had really fast feet, but it tended to go, taptaptatap, it just kept going on and on rather than having breaks and different rhythms. And with tap you’ve got to try and make music with it rather than dancing along to music. Once I sort of realised that, I started to work that way. For example, in Tap Dogs, half of the show has got no music whatsoever; it’s just the rhythm of the feet. And then a lot of the tracks that were developed for Tap Dogs started off with the feet, then music was added in.

You can be a good tap dancer, but you’ve got to have a point of difference. In any business, the point of difference makes your product special. With Tap Dogs we had an industrial set, all steel and ladders and pulleys and ropes and different surfaces that the dancers used to create different sounds. And even today, if your sound guy isn’t very good or takes shortcuts, you can lose all the tiny little beats in the taps and you’re only getting the high notes. So amplifying it properly and having a good sound technician is key, especially once the music track or drummers come in. That’s how we were different.

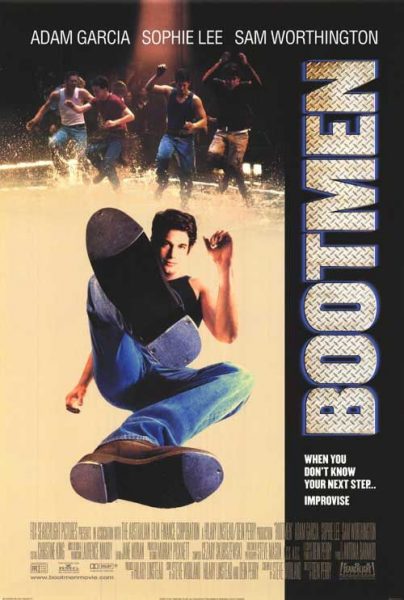

CD: And then you developed the film Bootmen (2000). So how did that come about?

CD: And then you developed the film Bootmen (2000). So how did that come about?

DP: About a year into Tap Dogs performing I filmed the show over four nights in London with a really good director, Aubrey Powell. He was a live performance specialist and did a great job, but that was really early on in the show’s life. A show develops, so it doesn’t stay the same. The core structure will stay the same, but over many years, routines evolve. So, when you look back on the video of Tap Dogs, it was filmed in 1997 probably and it’s very little compared to what it is now.

I thought, if there’s ever going to be an opportunity to make a film, this is the time … the hype was high and everyone knew about Tap Dogs. We’d been on the Jay Leno show five times over our and people in Hollywood knew us. ‘Surely they’ll let us in the door to talk?’ So I hired a writer, Steve Worland, who’s done a fair few films, and he came on tour with us. I paid him to come on tour and write a treatment up. I didn’t want it to be exactly us about us, but for Tap Dogs to be his inspiration. So he put two brothers into the story because I’ve got a brother, for example. He went back home and wrote a treatment, then we read it, and then we worked on it. Then we got other people who analysed scripts of treatments. When we got it to a point where we thought it was pretty good, we sent it to all the studios in Hollywood and the film finance corp here. It was a three-year process. A pitch we built from nothing. And it took a long time. By 1999 we had it funded 50/50 by Fox Studios in the US and the film finance corp here in Australia. The budget was eight and a half million which was small for a proper feature film. But we went back and asked for another million to do some reshoots towards the end for a stronger finish and a few other things that weren’t really working.

I made Bootmen because I wanted to be able to get our style of dance into a feature film. I thought it was going to be our only chance before somebody else copied us and did it. And I thought if the film is only half-successful, it will give Tap Dogs longevity, and that’s the two main reasons I did it. To get some of the tap dancing onto the silver screen, and then if it works, it will make the show run longer because a whole bunch of different people in different countries will get to know It. That’s what it was all about, and it did its job.

CD: And what would you say to dancers coming through now that have an absolute passion for tap? What are their opportunities going forward and what can they do to increase the industry for tap dancers?

DP: Well, the difference now from when I was in my twenties is that you’ve got YouTube and social media now. That’s a real big thing. And there weren’t any tap festivals back then. There’s a bunch tap dancers now that call themselves ‘the tap family’ and, while I’m not completely in that click, I think it’s fabulous. They all get to get together for a week or two and learn more skills. They come up through the ranks and become mentors and then they’ll get picked up go to a different country to be one of teachers there. There are many more tap dancers now than when I was doing it. It was just me and my brother and a few other guys really, or they stopped after their Eisteddfod days were finished, because there was no tap company or anything like that to move into.

So, if you look at people like Sarah Reich and Melinda Sullivan … as far as female tap dancer go, I think Sarah Reich is right up there with Gregory Hines, maybe even better… I think she’s extraordinary. I worked with Melinda on a show in Vegas about two years ago; she was my assistant as choreographer there. Sarah seems to have made a life for herself as a tap dancer without being in a show, without having to be in a company, without being in a show, she’s just Sarah, Sarah Reich. And so anyone that asks you that question, I would direct them straight to her website and her Facebook page and her Instagram. Have a look at what she’s done and how she’s survived and how she makes a living out of it. She travel as the world, she would go on teaching festivals. She ends up on other people’s film clips and an array of different things. She’s made her own album, her own tap album, which is a music album. She’s extraordinary.

I think every dance form keeps evolving. So the tap dancers today, compared to what we were doing, are on another level.

CD: So now you’ve developed your Tap Pups school. Is that your breeding ground for the next generation of Tap Dogs? To give back to the community and upskill the next generation?

DP: Exactly! I’ve been teaching Tap Pups now for probably 20 years. But really, it started with teaching my son, Reid Perry, a couple of steps in the garage. And then we moved up to a little hall off the road in Randwick where we were living. And then a couple of his mates that he was playing soccer with, their parents heard about it and asked to bring their boys along. Two kids joined us, Jamie Reisin and Jonah Ende, who were about 5 or 6. As we grew we moved to a Bondi studio and put in a proper floor where we’ve been at now for about 14 years.

So going back to your question. I teach an open class on Wednesday nights, which is just a drop in class for anyone that comes in. Reid deliberately doesn’t take any teaching himself on that night because he wants to join in with the old crew. Jonah went overseas to develop his tap dancing further at the Tapestry Dance Company and did the Jacob’s Pillow. He’s really good now. And Jamie’s been doing gigs and working. It was funny just at our first class back this year when the three of them turned up to class on Wednesday night, all as 24 year olds now.

So going back to your question. I teach an open class on Wednesday nights, which is just a drop in class for anyone that comes in. Reid deliberately doesn’t take any teaching himself on that night because he wants to join in with the old crew. Jonah went overseas to develop his tap dancing further at the Tapestry Dance Company and did the Jacob’s Pillow. He’s really good now. And Jamie’s been doing gigs and working. It was funny just at our first class back this year when the three of them turned up to class on Wednesday night, all as 24 year olds now.

So yeah, they are the next generation of Tap Dogs. Reid’s performed with the show before COVID in South Africa, London, Asia, and the United States, and replayed the key role in the show, which was Ben Read‘s original role (1994-2002). So yeah, Reid’s a Tap Dog now. It is a special breed of guy that can actually go out and do it every night as well, because it’s really tough show. You’ve only got six guys and you’ve got to keep going, going and going for an hour and a half without an interval. You’re dripping in sweat after 10 minutes, and you’ve got to entertain the crowd to keep them in engaged. You have got to be pretty mentally strong to keep it up, because the thing is, you’ve done it that night, you’ve had a great night, you’ve got to wake up and you’ve got to do it again the next day. And then its two days of that week where you’ve got to do it twice and you are going to have an hour and a half, two hour break in between and the show can only afford to take two swings. So you can only rotate so much.

CD: So is it still a male-only show? Or are there any females in the show?

DP: We’ve got female drummers. So that was a change we did a long time ago actually, and that’s a good dynamic to have. We’ve got a Japanese drummer Noriko, the last drummer we had with Noriko was Caitlin who was Cindy Lauper’s drummer. And she’s a rock and roll drummer and she’s fabulous. I mean, and these two girls together are unbelievable. About 15 years ago, we did a rebooted version of the show where we added three girls on stage with the six guys and it just didn’t really work. There was something about it and it just didn’t really work. I don’t know why.

CD: What is it that you love most about teaching the next generation?

DP: I just love their enthusiasm for it. I like to teach people who want to be taught. We started off with just boy classes for a while to encourage boys to come to the class, because we all know when there’s one or two boys in a class full of girls, they tend not to want to come back and they’re not with their mates, their ‘boy’ mates. So we found that by doing that the boys classes just went crazy, especially when Tap Dogs was in town and touring. These days, its more co-ed, our school is probably 85% boys.

What’s really fun for them is to put the Tap Pups on with the Tap Dogs. So you’ve got six strong Tap Dogs, tall-hardened guys that know how to entertain through tap dance, and then, you bring all these pups on and it is as cute as anything. We did this thing called the World Masters Games where I think there must have been about 70 pups come on to that stage once, and we had this massive catwalk and there was stacks of them. That was really fun. It’s been tough with COVID but we’re just trying to encourage everyone to get back in the studio.

***